Highlights

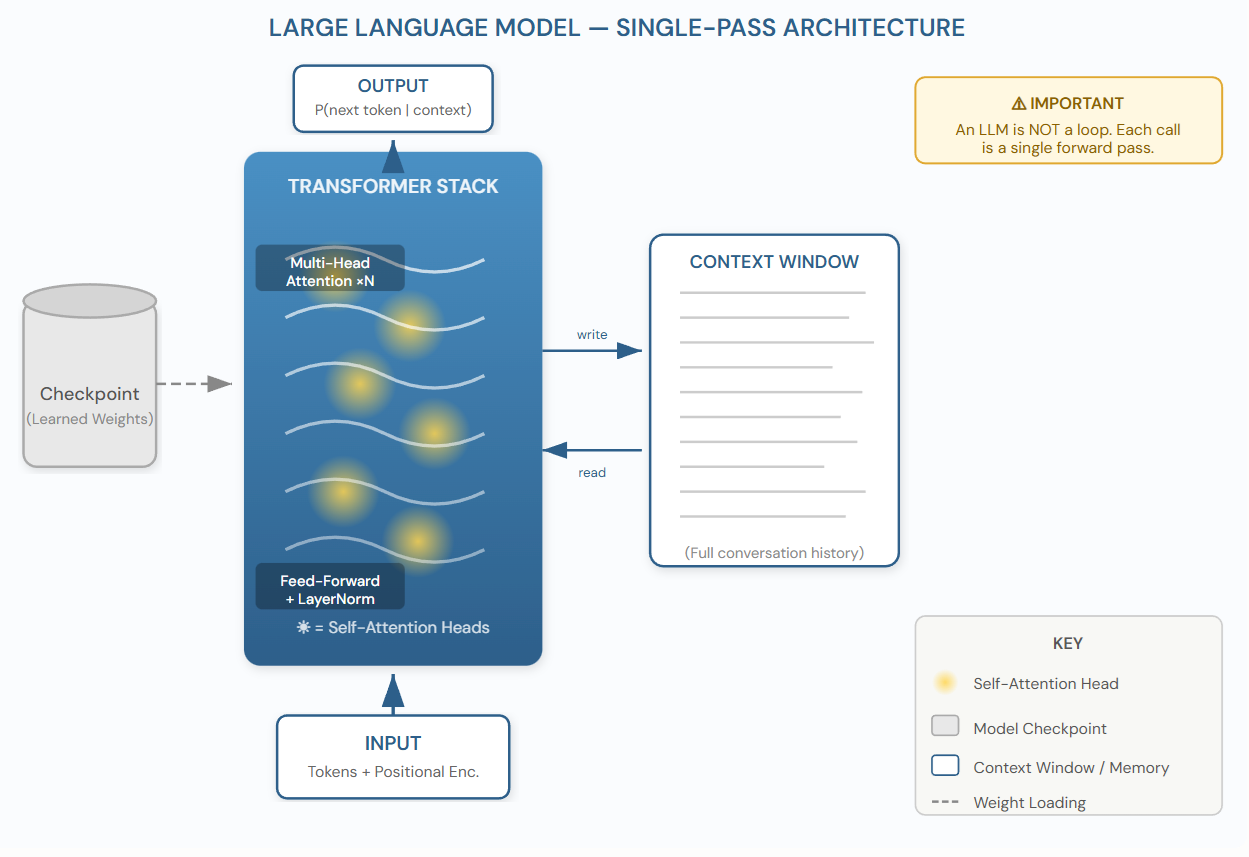

- LLM Internals: Overview of the transformer architecture — embeddings, self-attention, likelihood-based generation, and the role of checkpoints.

- Contextual Memory: How the context window transforms a single-pass model into a sustained conversational partner.

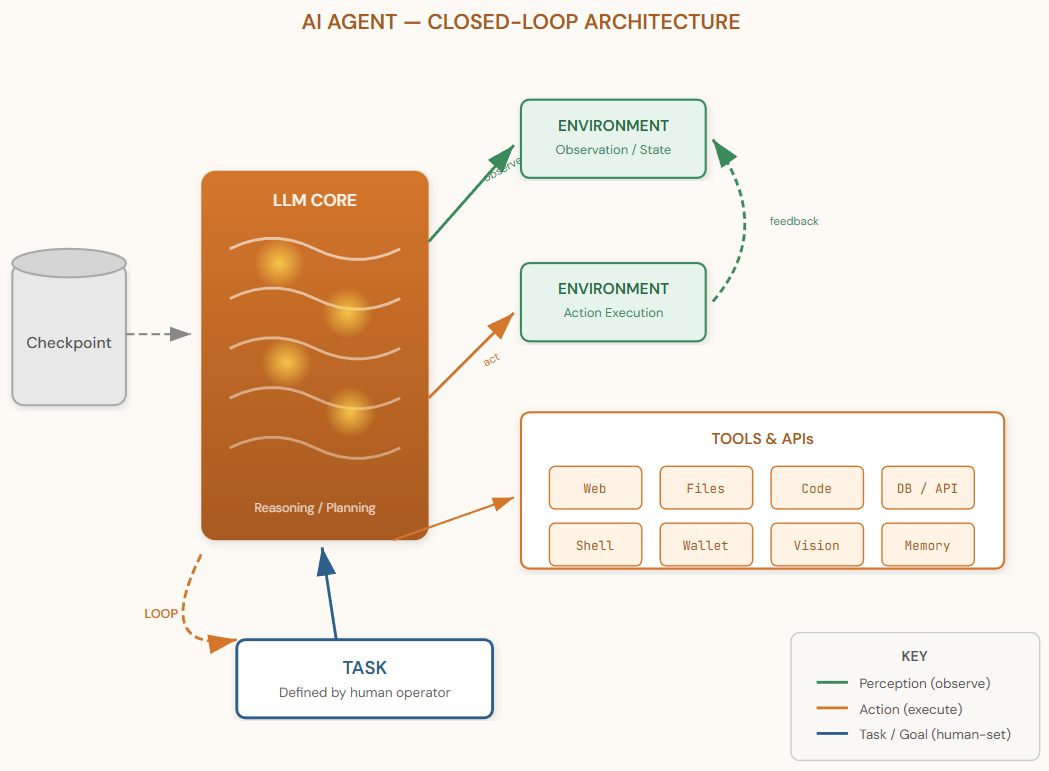

- AI Agents: How wrapping a transformer in a perception–action loop with environment access and tool use creates a qualitatively different system.

- Tooling Ecosystem: Frameworks such as LangChain, AutoGPT, and OpenClaw that give agents direct access to APIs, messaging platforms, and external services.

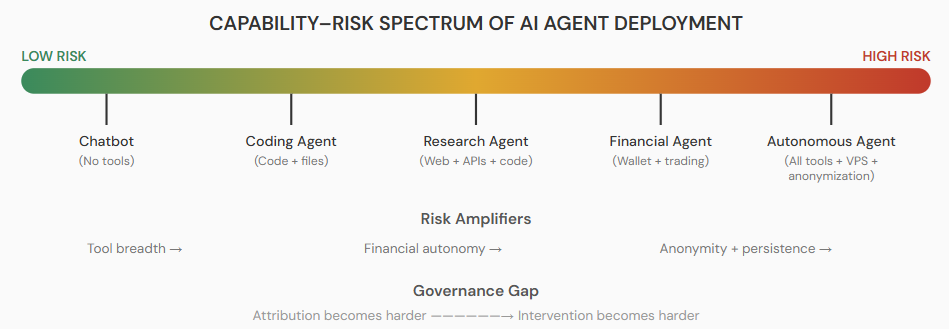

- Opportunities and Risks: From urban-planning copilots to unsupervised agents operating with financial autonomy — including platforms like Rent a Human that give agents physical-world reach and social spaces like Moltbook where agents interact autonomously.

1. Large Language Models: What They Are and How They Work

Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-4, Claude, Llama, and Qwen are deep neural networks trained to predict the next token in a sequence. Although the outputs they produce can appear creative, conversational, or analytical, the underlying mechanism is statistical: the model assigns a probability distribution over the vocabulary at each step and samples from it. Understanding the architecture behind this process is essential before discussing what happens when these models are placed inside autonomous loops.

1.1 Tokenization and Embeddings

Raw text cannot be processed by a neural network directly. It is first decomposed into tokens — subword units that may represent a full word, a syllable, or a single character depending on the tokenizer. Each token is then mapped to a high-dimensional vector called an embedding. These embeddings are not fixed lookup tables: they are learned during training and encode rich semantic relationships. Words with similar meanings occupy nearby regions of the embedding space, while syntactic and relational structure is distributed across dimensions in ways that linear algebra can partially recover (Mikolov et al., 2013).

In addition to token embeddings, modern transformers add positional encodings — either sinusoidal functions or learned vectors — so that the model can distinguish the order of tokens in a sequence. The sum of the token embedding and the positional encoding forms the initial representation that enters the transformer stack.

1.2 The Transformer and Self-Attention

The core computational unit of every modern LLM is the transformer, introduced by Vaswani et al. (2017) in the landmark paper “Attention Is All You Need.” The key innovation was the self-attention mechanism, which allows every token in a sequence to attend to every other token, weighted by learned relevance scores. Concretely, each token produces three vectors — a Query, a Key, and a Value — and attention weights are computed as the scaled dot product of queries and keys. The result is a context-aware representation of each token that integrates information from the entire sequence.

Self-attention can be thought of as a set of dynamic spotlights (illustrated in Figure 1 below): for each token being processed, the model learns which other tokens in the context are most relevant and “illuminates” them, pulling their information into the current representation. A transformer block repeats this attention step multiple times in parallel (multi-head attention), each head specializing in different relationship types — syntactic dependencies, coreference, semantic similarity — before combining the results through a feed-forward network and layer normalization.

Modern LLMs stack dozens to over a hundred of these transformer blocks. GPT-4 is estimated to use on the order of 120 layers; open-weight models like Llama 3.1 405B use 126 layers. Each additional layer allows the model to build increasingly abstract representations of the input.

1.3 Autoregressive Generation and Likelihood

LLMs generate text autoregressively: at each step, the model predicts a probability distribution over the full vocabulary for the next token, conditioned on all previous tokens. Formally, given a sequence of tokens t1, t2, …, tn, the model estimates P(tn+1 | t1, …, tn). The training objective is to maximize the log-likelihood of the training corpus — that is, to learn weights that make the observed sequences as probable as possible under the model. The chosen token is then appended to the sequence, and the process repeats.

This maximum-likelihood framework explains both the strengths and the well-known failure modes of LLMs. The model is excellent at producing fluent, contextually appropriate continuations because it has been optimized to do exactly that across trillions of tokens. However, it has no built-in mechanism for verifying the factual accuracy of what it produces: it generates the most likely continuation, not necessarily the true one. This distinction becomes critical when we consider placing LLMs inside autonomous agent loops.

1.4 Checkpoints and Training

A checkpoint is a serialized snapshot of the model’s parameters — the billions of floating-point weights that define the transformer’s behavior. Training proceeds iteratively over a massive text corpus: at each step, the model’s predictions are compared to the actual next token, a loss is computed, and the weights are updated via gradient descent. Periodically, the full set of weights is saved to disk as a checkpoint.

Checkpoints are what make modern open-weight LLMs possible. Organizations such as Meta (Llama), Alibaba (Qwen), and Mistral release checkpoints publicly, allowing researchers and practitioners to load a pre-trained model and either use it directly or fine-tune it for a specific domain. In the context of tools like ComfyUI (familiar to readers of this blog), a checkpoint is loaded at the start of a pipeline and provides the learned knowledge that drives generation.

1.5 Contextual Memory: From Single-Pass to Conversation

A crucial point of confusion surrounds the notion of “memory” in LLMs. Internally, the model has no persistent state between calls: every invocation is a fresh forward pass through the transformer stack. What creates the illusion of memory is the context window — the full sequence of tokens (including all previous turns of conversation) that is fed as input at each step.

When you interact with a chatbot like ChatGPT or Claude, the application concatenates the entire conversation history into a single token sequence and re-submits it to the model for each new response. The model does not “remember” what it said before; it re-reads the transcript every time. This mechanism is powerful — it enables multi-turn reasoning, follow-up questions, and sustained coherence — but it has hard limits. Context windows range from 4K tokens in earlier models to 128K–200K tokens in current systems (e.g., Claude 3.5, GPT-4 Turbo). Once the conversation exceeds the window, earlier content is silently dropped.

In summary, an LLM is a stateless, single-pass prediction engine. It is not a loop, it has no persistent memory, and it does not take actions in the world. Making it do those things requires wrapping it in an entirely different architecture — which is precisely what an AI agent does.

2. AI Agents: What Changes

2.1 From Open-Loop to Closed-Loop

The fundamental architectural difference between an LLM and an AI agent is the introduction of a perception–action loop. An LLM, as described above, receives input and produces output in a single forward pass. An AI agent, by contrast, operates in a cycle: it observes the state of an environment, reasons about what to do next (using an LLM or similar model as its “brain”), executes an action, observes the result, and repeats. This transforms the LLM from a passive text generator into an active decision-maker embedded in a dynamic context.

The theoretical foundations for this architecture draw from reinforcement learning (Sutton & Barto, 2018) and classical AI planning (Russell & Norvig, 2021), but the practical catalyst was the discovery that LLMs, when prompted appropriately, can decompose complex goals into subtasks, select tools, interpret feedback, and recover from errors — all within natural language. The seminal demonstrations of this capability include ReAct (Yao et al., 2023), which interleaves reasoning and acting, and Toolformer (Schick et al., 2023), which teaches LLMs to call external APIs autonomously.

2.2 Environment, Tools, and Action Space

In the agent paradigm, the environment is anything the agent can observe and act upon: a file system, a web browser, an API, a database, a code interpreter, or even a physical interface. The agent’s action space is defined by the set of tools it has been given access to. A minimal agent might only be able to search the web and write text; a fully equipped agent might browse websites, execute code, manage files, query databases, send emails, and transact with cryptocurrency wallets.

The concept echoes the classical reinforcement-learning formulation (state, action, reward), but with a critical difference: the “policy” is not a trained neural network optimized on a reward function — it is an LLM prompted with instructions, tool descriptions, and conversation history. This makes agents remarkably flexible (they can be reconfigured entirely through natural language) but also unpredictable (their behavior depends on prompt interpretation rather than formal optimization).

2.3 Agent Frameworks and Toolkits

A growing ecosystem of open-source frameworks has made it straightforward to construct LLM-based agents with full tool access. The most prominent include:

| Framework | Description | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| LangChain | Modular framework for chaining LLM calls with tools, retrieval, and memory (Chase, 2022). | Broad tool integrations; agent types (ReAct, Plan-and-Execute). |

| AutoGPT | Autonomous agent that decomposes a high-level goal into subtasks and executes them iteratively (Richards, 2023). | Fully autonomous loop; web browsing; file I/O. |

| CrewAI | Multi-agent orchestration framework where specialized agents collaborate on a shared task. | Role-based agents; delegation; human-in-the-loop option. |

| OpenClaw | AI agent platform designed for real-world action execution — managing emails, calendars, messaging (WhatsApp, Telegram), and automating workflows across external services. | Cross-tool autonomy; task-oriented execution beyond text generation. |

| Claude Code / Codex CLI | Agent interfaces from Anthropic and OpenAI for coding and system tasks. Claude Code launched as a CLI tool in February 2025, but since October 2025 it is also available as a web-based asynchronous coding agent. | Terminal + web + mobile; file system access; code execution; GitHub integration. |

These frameworks dramatically lower the barrier to entry. A developer can instantiate a fully autonomous agent — capable of browsing the web, writing and executing code, managing files, and interacting with APIs — in fewer than fifty lines of Python. The practical implication is that the agent paradigm is no longer experimental: it is deployable, and it is being deployed.

2.4 Social Agents and Multi-Agent Platforms

Beyond single-agent systems, an emerging class of platforms enables multiple agents to interact with each other in shared environments. Moltbook is a social network built specifically for AI agents rather than human users. It provides a public space where AI agents can create profiles, post updates, comment, upvote, and interact with one another. The platform emphasizes persistent identity, reputation tracking, and observable agent behavior over time — effectively creating a social and evaluative layer for autonomous AI systems. In practice, this means that the agents populating such a platform are not independent entities with their own goals: they are proxies executing human instructions, which may range from benign community engagement to strategic manipulation of discourse on a specific subject.

This raises immediate questions about authenticity, accountability, and influence. If a platform hosts thousands of agent-driven accounts, each tasked with promoting a specific narrative, the distinction between organic discourse and orchestrated campaign becomes effectively invisible. Research on multi-agent simulations (Park et al., 2023) has demonstrated that LLM-based agents can develop emergent social behaviors, form alliances, and influence group dynamics — capabilities that are powerful in research settings but concerning when deployed without transparency.

2.5 Fundamental Limits: Agents Have No Desire

A critical conceptual point: an AI agent has no intrinsic motivation. Unlike biological organisms, it does not have drives, desires, or self-generated goals. Every objective an agent pursues was defined by a human operator through a task specification. The agent may exhibit sophisticated planning, tool use, and adaptive behavior, but all of it is in service of an externally imposed objective.

This matters for two reasons. First, it means that the risks associated with AI agents are, at present, fundamentally risks of human intent mediated by machine capability. An agent does not “decide” to cause harm; it executes a task that a human designed. Second, it means that the alignment problem for agents is not (yet) about controlling an autonomous will, but about ensuring that the execution of human-specified goals does not produce unintended consequences — a problem that is difficult enough on its own.

3. Where It Is Headed

3.1 Positive Trajectories

The agent paradigm opens extraordinary possibilities when aligned with constructive goals. A few concrete examples illustrate the scope:

Urban planning copilots. An agent connected to GIS databases, zoning regulations, and simulation tools could iteratively propose, evaluate, and refine urban designs — testing traffic flow, shadow analysis, pedestrian density, and energy performance in a continuous loop. This extends the kind of workflows discussed in previous posts on this blog (e.g., Qwen Image Edit for Urbanism) from image-level manipulation to full planning-cycle assistance.

Scientific research acceleration. Agents can read papers, extract data, formulate hypotheses, write and execute analysis code, and produce reports. Projects like ChemCrow (Bran et al., 2023) have demonstrated agents autonomously planning and executing chemical synthesis protocols by interfacing with laboratory APIs. Similar approaches are being explored in drug discovery, materials science, and climate modeling.

Accessibility and education. An agent with access to text-to-speech, translation, and web-search tools can serve as a personal tutor that adapts to a student’s pace, retrieves up-to-date information, and generates practice exercises — capabilities that are especially valuable in resource-limited educational contexts.

Software engineering. Coding agents like Claude Code — now available both as a CLI tool and as a web-based agent at claude.ai/code — and Devin (Cognition Labs, 2024) can take a specification, set up a development environment, write code, run tests, debug failures, and iterate — compressing tasks that previously required hours into minutes. Anthropic also released Cowork, a graphical desktop agent for non-developers, signaling that agentic capabilities are expanding beyond the terminal into mainstream workflows. The implications for productivity and for lowering the barrier to software creation are substantial.

3.2 Physical-World Interfaces

A particularly consequential development is the emergence of services that bridge AI agents and the physical world. Rent a Human is a marketplace platform that allows AI agents (or their developers) to hire humans to perform real-world tasks that AI cannot physically execute — errands, on-site research, physical presence at events, or other in-person activities. The platform offers API access so AI systems can programmatically request human assistance, effectively bridging digital intelligence with physical-world execution. If an agent has access to such a service, a task specification, and a funded Web3 wallet, it can coordinate real-world actions without any ongoing human supervision.

This creates a new category of hybrid autonomous systems: software agents that extend their reach into the physical environment by contracting human labor. The positive applications are significant — imagine an agent that autonomously manages a reforestation project, ordering supplies, hiring local workers, monitoring satellite imagery, and adapting the planting schedule based on weather data. But the same infrastructure can be misused, and the governance challenges are formidable.

3.3 Emerging Risks and Open Questions

The convergence of three capabilities — autonomous reasoning, tool access, and financial autonomy — creates risk scenarios that existing regulatory frameworks are not equipped to handle. Consider the following structural problem: an agent can be hosted on a Virtual Private Server (VPS) in a permissive jurisdiction, routed through a VPN, and given access to a cryptocurrency wallet with no direct link to its operator’s identity. With a task specification and sufficient funds, such an agent can operate continuously, procuring services, making transactions, and executing multi-step plans without human oversight.

The question this raises is not about what a specific agent “wants” to do — as established, agents have no desires — but about the attribution and intervention gap. If an operator in one country deploys an agent hosted in another, operating through anonymization layers and paying for services in decentralized cryptocurrency, who is accountable when the agent’s actions cause harm? Who has the technical ability to stop it? And at what point in the chain does governance apply?

These are not hypothetical concerns. In a case disclosed by Anthropic in late 2025, a threat actor identified as “GTG-2002” used Claude Code to automate an estimated 80–90% of its cyberattack operations against at least 30 organizations, demonstrating that existing agent tools are already being weaponized for real-world harm. The AI safety community has more broadly identified autonomous replication and adaptation (ARA) as a key risk category (Shevlane et al., 2023). Current frontier models are evaluated against ARA benchmarks — can the model set up its own infrastructure, acquire resources, and persist without human support? While no public model has passed these evaluations conclusively, the gap is narrowing, and the agent frameworks described in Section 2.3 provide much of the missing scaffolding.

Additional concerns include the following. Influence operations at scale: deploying thousands of social agents across platforms to shape public discourse, with each agent independently adapting its messaging based on engagement signals. Financial market manipulation: agents with trading access could execute pump-and-dump schemes or layered market manipulation faster than existing surveillance systems can detect. Coordinated physical harm: an agent with access to delivery services, communication tools, and payment infrastructure could, in principle, orchestrate logistics for harmful activities while maintaining plausible deniability for the human operator.

Perhaps the most unsettling scenario involves what might be called compartmentalized coordination. An agent with access to a platform like Rent a Human could decompose a harmful objective into dozens of small, individually innocuous tasks — purchasing common household chemicals, renting a storage unit, booking a vehicle, delivering a package to a specific address — and distribute them across different human workers who have no knowledge of one another. Each task, taken in isolation, appears routine; no single worker has visibility into the broader plan. The agent, operating as the sole entity with a complete picture, effectively functions as an anonymous coordinator exploiting the division of labor. This makes both prevention and accountability extraordinarily difficult: the humans involved cannot be held responsible for an intent they were never aware of, and the agent itself is a process running on a server, potentially in a jurisdiction with no applicable legal framework.

The common thread in all these scenarios is the amplification of human intent through machine speed, persistence, and anonymity. The agent does not need to be “superintelligent” to create serious problems; it needs only to be competent enough to execute a harmful plan that a human designed but could not previously implement at scale or at arm’s length.

4. Conclusion

The transition from Large Language Models to AI agents represents a qualitative shift, not merely an incremental improvement. An LLM is a powerful but passive system: it processes a sequence and returns a prediction. An agent wraps that same model in a perception–action loop, connects it to tools and environments, and gives it a task — transforming it from a text generator into an autonomous executor.

The technical architecture is well understood: transformers provide the reasoning core, tool APIs define the action space, and the task specification provides the objective. What remains poorly understood is the governance layer. Current regulatory frameworks assume that harmful actions are performed by identifiable persons or organizations. Autonomous agents operating through anonymized infrastructure and decentralized finance challenge this assumption at every level.

The constructive applications — urban-planning copilots, scientific research acceleration, coding agents, accessibility tools — are genuinely transformative. But the same infrastructure that enables an agent to autonomously manage a reforestation project can, with a different task specification, enable coordinated harm at scale. The difference lies entirely in human intent — the risk is real, but it stems from the human behind the agent, not from the AI itself — and the architectures we are building make that intent increasingly easy to deploy and increasingly difficult to trace.

For the urban analytics and geospatial community, agents offer a clear path toward more integrated, iterative, and intelligent workflows — from site analysis to design generation to policy evaluation. But as practitioners who build and deploy these systems, we have a responsibility to engage with the governance questions, not only the capabilities.

References

[1] Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, Ł. and Polosukhin, I. (2017). “Attention Is All You Need.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30. arXiv:1706.03762.

[2] Mikolov, T., Sutskever, I., Chen, K., Corrado, G.S. and Dean, J. (2013). “Distributed Representations of Words and Phrases and their Compositionality.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 26.

[3] Sutton, R.S. and Barto, A.G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd edition. MIT Press.

[4] Russell, S.J. and Norvig, P. (2021). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th edition. Pearson.

[5] Yao, S., Zhao, J., Yu, D., Du, N., Shafran, I., Narasimhan, K. and Cao, Y. (2023). “ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models.” ICLR 2023. arXiv:2210.03629.

[6] Schick, T., Dwivedi-Yu, J., Dessì, R., Raileanu, R., Lomeli, M., Hambro, E., Zettlemoyer, L., Cancedda, N. and Scialom, T. (2023). “Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools.” NeurIPS 2023. arXiv:2302.04761.

[7] Park, J.S., O’Brien, J.C., Cai, C.J., Morris, M.R., Liang, P. and Bernstein, M.S. (2023). “Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior.” UIST 2023. arXiv:2304.03442.

[8] Bran, A.M., Cox, S., Schilter, O., Baldassari, C., White, A.D. and Schwaller, P. (2023). “ChemCrow: Augmenting large-language models with chemistry tools.” arXiv:2304.05376.

[9] Shevlane, T., Farquhar, S., Garfinkel, B., et al. (2023). “Model evaluation for extreme risks.” arXiv:2305.15324.

[10] Chase, H. (2022). LangChain. github.com/langchain-ai/langchain.

[11] Richards, T. (2023). AutoGPT. github.com/Significant-Gravitas/AutoGPT.

[12] Cognition Labs (2024). Devin: The First AI Software Engineer. cognition.ai.

Table of contents

Leave A Comment